How

Many Divisions Has the Caliph?

Tech Central Station ^ | 18 Jan 2006 | James Pinkerton

Posted on 01/23/2006 10:49:00

PM PST by Lorianne

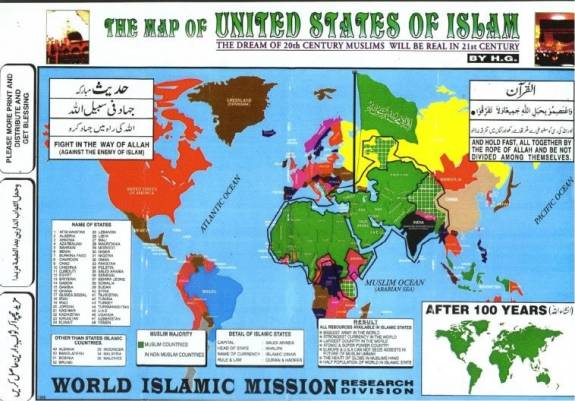

Should the Caliphate be reunited? It depends on whom you ask.

Osama Bin Laden is for such a reunification of all Muslims,

which is surely enough to persuade most Americans to oppose

it.

But could the Caliphate be reunited? That seems to be a somewhat

increasing prospect. Right now, to be sure, it’s a cloud on

the horizon no bigger than a fist, but some important people

are alarmed enough about the possibility to take time to denounce

it. That’s right, some big people -- as big as George W. Bush.

Last October, in making his case on Iraq, the President upped

the ante further; he warned the National Endowment for Democracy

that if the US lost in Iraq, the consequence could be a New

Caliphate. Speaking of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi & Co., Bush

spun out a grim scenario:

“The militants believe that controlling one country will rally

the Muslim masses, enabling them to overthrow all moderate governments

in the region, and establish a radical Islamic empire that spans

from Spain to Indonesia. With greater economic and military

and political power, the terrorists would be able to advance

their stated agenda: to develop weapons of mass destruction,

to destroy Israel, to intimidate Europe, to assault the American

people, and to blackmail our government into isolation.”

On Saturday, The Washington Post raised the specter of a Caliphate

yet again. The subheadline on the front page read, “Restoration

of Caliphate, Attacked by Bush, Resonates with Mainstream Muslims.”

Reporter Karl Vick, writing from Turkey, cited polls showing

that an increasing number of Muslims view America as leading

an assault on Islam.

That’s a controversial argument, of course, but it’s noteworthy

that Vick must have written the bulk of his 2200-word story

before the incident in Pakistan in which the US apparently failed

in its attempt to bump off Bin Laden lieutenant Ayman al-Zawahiri.

The headline in the online publication PakTribune bannered:

“Islamabad lodges protest with US over Bajaur Airstrike/Rashid

expresses grief over colossal loss of lives in Bajaur air raid.”

And that anti-American spin wasn’t confined to Pakistan; the

headline of the Tory-tilting Telegraph in London was about the

same: “Pakistan fury as CIA airstrike on village kills 18.”

One need only scan the headlines, detailing rising Islamic

fervor around the world, from England to Chechnya to Indonesia,

to conclude that something is stirring in the Muslim mind. Some

say it’s a religious revival that will bring theocracies in

lands Muslims control. Others say it’s the beginning of Islamic

democracy. It’s impossible to know for sure what it is, but

it’s certainly hard to argue that these Islamist stirrings are

pro-Western. That is, whatever the Muslims are up to, it seems

as if they are reshaping their own internal relations, substantially

in reaction to what they see as the encroachment, or even onslaught,

of others, particularly the Americans. The point here isn’t

to take their side, but to try to understand, at least, what’s

going on, before we decide what we should do.

The gloomiest observers, such as Michael Scheuer, have argued

that this is what Bin Laden has had in mind all along: a clash

of civilizations that would unite not only the Arab world against

the West, but also the larger Muslim world, including such non-Arab

Muslim countries as Pakistan.

In the wake 9-11, Bin Laden played the anti-Western card in

his stealth-televised address of October 7, 2001, in which he

declared, “What the United States tastes today is a very small

thing compared to what we have tasted for tens of years. Our

nation has been tasting this humiliation and contempt for more

than 80 years.”

The “nation” in question, experts agree, was the selfsame Caliphate.

And the “80 years” referred to the passage of time since the

Treaty of Sevres, which dissolved the Ottoman Empire, the last

incarnation of that Caliphate. Sevres, by the way, was the companion

treaty to the better-known (at least in the West) Treaty of

Versailles, which formally ended World War One between Germany

and the Allies.

In other words, Bin Laden was seeking to fuse his message in

the twinned language of religion and nationalism -- being both

mindful and thankful, one supposes, that “separation of mosque

and state” is not much of a concept in the Islamic Ummah. Indeed,

Uthman, the third Caliph, way back in the 7th century CE, is

remembered for his enormous politico-military power (he added

Iran and most of North Africa to the new Muslim empire) and,

at the same time, for his vast spiritual influence (he ordered

the standardization of the Qur’an worldwide). So it’s interesting

and ominous that, 15 centuries later, al-Qaeda calls its Internet

newscast, which debuted last year, “The Voice of the Caliphate.”

In Bin Laden’s mind, Arab unity, and Muslim unity, are the

key to regaining Islam’s influence in the world. And Bin Laden

has a point: Unity has always been a route to power. Such major

countries/empires as England, France, Spain, Germany, Italy,

and Russia were all once just a bunch of fighting fiefdoms;

only political unity made them strong -- although, of course,

not always to the benefit of their neighbors. And closer to

home, what would be said of American power if the 13 colonies

hadn’t united, and then stayed united?

Today, in a world of superpowers, such as the US and China,

plus rising powers such as India and Brazil, the Arabs and Muslims

are small and divided.

As for the 300 million people in the Arab world, they are divided

into the 22 different members of the Arab League. So how would

one go about recreating even a “core” Caliphate? Where for example,

would the capital be, when the historic seats of Arab Muslim

power are five in number: Mecca, Medina, Baghdad, Damascus,

and Cairo? And what of the oftentimes murderous distinction

between Shia and Sunni, not to mention dozens of smaller Muslim

sects, such as the Alawites?

And of course, most of the 1.3 billion or so Muslims in the

world aren’t even Arab. The Organization of the Islamic Conference

includes 56 members, as disparate as Albania and Afghanistan,

Cameroon and the Comoros Islands, Morocco and Malaysia, Uganda

to Uzbekistan. What are the chances of all those people, stretched

across three continents, getting together?

And it must be noted that the rest of the world has not been

eager to see Arabs and Muslims unified. Let’s face it: the strategy

of divide-and-conquer works. Fans of the 1962 movie “Lawrence

of Arabia” will remember that at the end, to T.E. Lawrence’s

regret, the Arabs, recently freed from the Turks, were unable

to come up with a unity plan of their own. And yet the European

powers, most notably Great Britain and France, were perfectly

happy back then to see the Arabs disunited -- and thus easily

colonized. In the film, Alec Guinness, playing Prince Feisal,

the would-be leader of Greater Arabia, thwarted in his ambitions

by the victorious Europeans, says that the new white masters

doubtless have “reports to make upon my people and their weakness,

and the need to keep them weak in the British interest... and

the French interest too, of course. We must not forget the French

now.”

Even now, after more than four years of war with Islamic elements,

most Americans probably have no idea about any of this history,

and thus no understanding of what either Bush or Bin Laden are

talking about when they refer to the Caliphate, once or future.

One reason for this national cluelessness is that it’s easy

to be mellow about geopolitics when one is large and in charge.

That’s certainly true for the United States, as it exercises

unchallenged, and unchallengeable, economic and military suzerainty

over not only the Americas, but also Western Europe and much

of Africa and the Pacific. That’s a heckuva sphere of influence,

bolstered, of course, by strong regional allies such as the

United Kingdom, Australia, and Israel.

But Americans weren’t always so relaxed about power in their

proclaimed domain -- we won that power the hard way, by fighting

for it, and winning it. Ask the Native Americans. Ask the British.

Ask the Mexicans, or the Confederates, or the Spanish, or the

Germans or Japanese.

Today, America sits atop of what many -- not all of them critics

-- consider to be a global empire. We inherited part of it,

in effect, from the Europeans, and yet we conquered or bought

much of the rest of it. And one can say it’s nice to be #1.

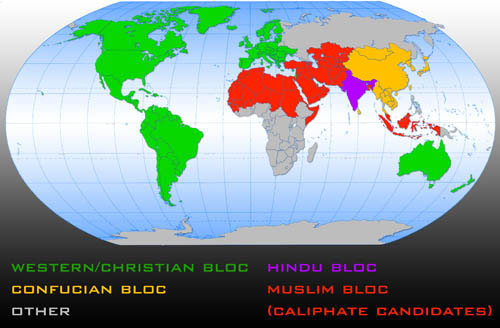

In effect, the US sits atop what might be called the “Western

Bloc,” or perhaps the “Christian Bloc” -- referring to the religious

heritage of the dominant population, if not necessarily their

current religious practice -- which stretches from Warsaw to

Washington DC, from Ottawa to Canberra, from London to Lima.

Parenthetically, we can leave Russia out of this grouping; one

reason Russia is not a strong country these days is that it’s

not really in an alliance with anyone. We can also note that

many countries in Latin America are increasingly hostile to

the Yanqui, but at the same time, no country south of the border

poses an unmanageable military or economic threat to Uncle Sam

-- and it will stay that way if all those many countries remain

quarreling and divided among themselves, as they have for the

past two centuries.

So regional blocs, based on a common characteristic, such as

religious and cultural ancestry, are naturally powerful. And

of course, if one country is the leader of such a bloc, it doesn’t

want a rival within that bloc to emerge -- and thus it can’t

be displeasing to American strategists that the European Union

is foundering. Just as Europeans were once eager to keep the

rest of the world divided, so we should not lament the failure

of a Brussels-based superstate to emerge as much more than a

costly red-tape dispenser. America is effectively unchallenged

within the Christian Bloc.

But there’s a problem dead ahead: As we look around the world,

we can see that other countries are forming blocs of their own,

too.

China, for example, is pulling together a Confucian bloc in

East Asia. The People’s Republic is an empire of its own, people-wise

and territory-wise, but it is now using its longer and longer

politico-economic hook to reel in as many of its neighbors as

it can.

And India, home to almost all the world’s Hindus, is a huge

one-country empire destined to spread its engorging power to

Hindus around the world, and especially to the lands touching

on the aptly named Indian Ocean.

So this is the environment in which the Arab/Muslim spirit

will arise, if it arises. Bin Laden sees clearly that he is

weak because his people, and his faith, are divided. Bush sees

it too -- and wants to keep it that way. That’s one reason we

are in Iraq and Afghanistan.

And perhaps someday in Iran, where the new leader in Tehran,

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, sees himself on a “divine mission”, which

includes, of course, nuclear weapons. We don’t want that for

them, of course, not just because of terror concerns, but because

an Iran possessed of both nuclear weapons and oil would be a

serious regional player, indeed. Could the Iranians go further?

Could they possibly pull together their own version of the Caliphate?

Probably not, because of their ferocious ethnic differences

with the Arabs -- but they might try.

That’s our ace in the hole: The Muslims, from Djibouti to Jakarta,

are so ethnically and culturally diverse that it’s hard to see

them Caliphating.

But as Washington Post reporter Vick made plain in his story,

the dream of a Caliphate will not die -- because Muslims remember

their strength in the past, see their weakness today, and dream

of being powerful in the future. Vick quoted one ordinary Turk

asking, “Why do you keep invading Muslim countries?” The man

continued, “I won’t live to see it, and my children won’t, but

one day maybe my children’s children will see someone declare

himself the caliph, like the pope, and have an impact.”

Ah yes, the pope. John Paul II, to name a recent pontiff. A

mere spiritual leader -- how much power could he wield in this

world? How many divisions does he have?

Yet many of those who dismissed the new Pope’s power when he

was named in 1978 -- all those atheist communist bureaucrats

in Warsaw and Moscow, for openers -- had been humbled, or worse,

by 2005.

So it is with spiritual power over the faithful and the impressionable:

Faith may or may not be able to move mountains, but as the Pope

proved, belief can change history. Most likely, it can change

future history, too. And say whatever one might about Islam,

it has plenty of faithful adherents, who will do just about

anything to preserve and expand its influence in the world today.

Which is why the Caliphate -- the idea of it, at least -- is

going to be a part of our future. Like it or not.