Do These Mysterious Stones Mark

the Site of the Garden of Eden

MailOnline

By

Tom Cox

28th February 2009

We offer here twin

articles on the same subject. The first article from the

Daily Mail, and the second from the Smithsonian. We do not agree at all with the Daily Mail’s

assertion that these stones mark the Garden of Eden. First the bible states that the garden that

God created was EAST of

The idea that child

sacrifices, and human sacrifices that were conducted in this temple would have

been some religious worship to God demonstrated the author’s complete lack of

knowledge of the word of God as recorded in the Bible and specifically in the

book of Genesis.

What the article is

talking about is a Pre-Flood of Noah Society and a picture into what God

destroyed and blotted out with the Flood of Noah by God’s wrath. Clearly according to the word of God the

worship and sacrifice here was not unto God

The idea though that

this was built, and used for however long it was used and then suddenly hand

buried to preserve the records carved in stone there is a direct indication

that these people knew of their pending judgment.

In another account of

Genesis that I have read, it indicates that God told Adam and Eve of two coming

judgments on men one would be by fire and one would be by water so that Adam

and Eve and their descendants made two sets of records one on stones, and the

other on clay. So that if the first judgment was by fire the stones would be

destroyed and the clay record would survive, and if the first judgment was by flood the clay would

be destroyed and the stone record would survive.

There is another book

that shows stone markers with writing that is described as Pre-Hebrew all over

the US Southwest and in other parts of the world describing things from pre-flood

Genesis. In a series of clay tablets from Sumner a king had recorded that he

liked reading pre-flood books

The book of Genesis

declares that men became artificers, and were able to write. And if we were to level a guess as to who may

have built this temple we would suggest from the bible Nimrod. As it is

recorded of him that he became a great hunter, and that he hunted the souls of

men. Both demonstrated in this temple

complex.

For the old Kurdish shepherd, it

was just another burning hot day in the rolling plains of eastern

The man looked left and right:

there were similar stone rectangles, peeping from the sands. Calling his dog to

heel, the shepherd resolved to inform someone of his finds when he got back to

the village. Maybe the stones were important.

They certainly were important.

The solitary Kurdish man, on that summer's day in 1994, had made the greatest

archaeological discovery in 50 years. Others would say he'd made the greatest

archaeological discovery ever: a site that has revolutionised

the way we look at human history, the origin of religion - and perhaps even the

truth behind the Garden of Eden.

A few weeks after his discovery,

news of the shepherd's find reached museum curators in the ancient city of

They got in touch with the German

Archaeological Institute in

As he puts it: 'As soon as I got

there and saw the stones, I knew that if I didn't walk away immediately I would

be here for the rest of my life.'

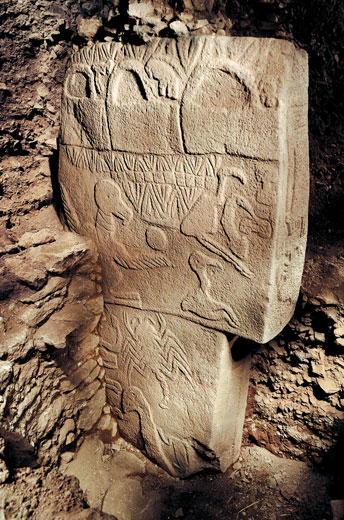

Remarkable

find: A frieze from Gobekli Tepe

(Behind the sitting flamingo and other bird we see what appears to be

bundled sheaves of grain)

Schmidt stayed. And what he has

uncovered is astonishing. Archaeologists worldwide are in rare agreement on the

site's importance. 'Gobekli Tepe

changes everything,' says Ian Hodder, at

David Lewis-Williams, professor

of archaeology at

Some go even further and say the

site and its implications are incredible. As

So what is it that has energised and astounded the sober world of academia?

The site of Gobekli

Tepe is simple enough to describe. The oblong stones,

unearthed by the shepherd, turned out to be the flat tops of awesome, T-shaped

megaliths. Imagine carved and slender versions of the stones of Avebury or

Most of these standing stones are

inscribed with bizarre and delicate images - mainly of boars and ducks, of

hunting and game. Sinuous serpents are another common motif. Some of the

megaliths show crayfish or lions.

The stones seem to represent

human forms - some have stylised 'arms', which angle

down the sides. Functionally, the site appears to be a temple, or ritual site,

like the stone circles of

To date, 45 of these stones have

been dug out - they are arranged in circles from five to ten yards across - but

there are indications that much more is to come.

Geomagnetic surveys imply that there are hundreds more standing stones, just

waiting to be excavated.

So far, so

remarkable. If Gobekli Tepe was simply this, it

would already be a dazzling site - a Turkish Stonehenge. But several unique

factors lift Gobekli Tepe

into the archaeological stratosphere - and the realms of the fantastical.

The site has

been described as 'extraordinary' and 'the most important' site in the world

(In this backside view we see carvings

on these two stones on the open side so that all these stones were carved at

least on two sides – the front and the right side)

The first is its staggering age.

Carbon-dating shows that the complex is at least 12,000 years old, maybe even

13,000 years old.

That means it was built around

10,000BC. By comparison, Stonehenge was built in 3,000 BC and the pyramids of

Gobekli is thus the oldest such site in the

world, by a mind-numbing margin. It is so old that it predates settled human

life. It is pre-pottery, pre-writing, pre-everything. Gobekli

hails from a part of human history that is unimaginably distant, right back in

our hunter-gatherer past.

How did cavemen build something

so ambitious? Schmidt speculates that bands of hunters would have gathered

sporadically at the site, through the decades of construction, living in

animal-skin tents, slaughtering local game for food.

The many flint arrowheads found

around Gobekli support this thesis; they also support

the dating of the site.

This revelation, that Stone Age

hunter-gatherers could have built something like Gobekli,

is worldchanging, for it shows that the old

hunter-gatherer life, in this region of Turkey, was far more advanced than we

ever conceived - almost unbelievably sophisticated.

It's as if the gods came down

from heaven and built Gobekli for themselves.

This is where we come to the

biblical connection, and my own involvement in the Gobekli

Tepe story.

About three years ago, intrigued

by the first scant details of the site, I flew out to Gobekli.

It was a long, wearying journey, but more than worth it, not least as it would

later provide the backdrop for a new novel I have written.

Back then, on the day I arrived

at the dig, the archaeologists were unearthing mind-blowing artworks. As these

sculptures were revealed, I realised that I was among

the first people to see them since the end of the Ice Age.

And that's when a tantalising possibility arose. Over glasses of black tea,

served in tents right next to the megaliths, Klaus Schmidt told me that, in his

opinion, this very spot was once the site of the biblical Garden of Eden. More

specifically, as he put it: 'Gobekli Tepe is a temple in

To understand how a respected

academic like Schmidt can make such a dizzying claim, you need to know that

many scholars view the

Seen in this way, the

But then we 'fell' into the

harsher life of farming, with its ceaseless toil and daily grind. And we know

primitive farming was harsh, compared to the relative indolence of hunting,

because of the archaeological evidence.

To date,

archaeologists have dug 45 stones out of the ruins at Gobekli

When people make the transition

from hunter-gathering to settled agriculture, their skeletons change - they

temporarily grow smaller and less healthy as the human body adapts to a diet

poorer in protein and a more wearisome lifestyle. Likewise, newly domesticated

animals get scrawnier.

This begs the question, why adopt

farming at all? Many theories have been suggested - from tribal competition, to

population pressures, to the extinction of wild animal species. But Schmidt

believes that the

'To build such a place as this,

the hunters must have joined together in numbers. After they finished building,

they probably congregated for worship. But then they found that they couldn't

feed so many people with regular hunting and gathering.

'So I think they began

cultivating the wild grasses on the hills. Religion motivated people to take up

farming.'

The reason such theories have

special weight is that the move to farming first happened in this same region.

These rolling Anatolian plains were the cradle of agriculture.

The world's first farmyard pigs

were domesticated at Cayonu, just 60 miles away.

Sheep, cattle and goats were also first domesticated in eastern

But there was a problem for these

early farmers, and it wasn't just that they had adopted a tougher, if ultimately

more productive, lifestyle. They also experienced an ecological crisis. These

days the landscape surrounding the eerie stones of Gobekli

is arid and barren, but it was not always thus. As the carvings on the stones

show - and as archaeological remains reveal - this was once a richly pastoral

region.

There were herds of game, rivers

of fish, and flocks of wildfowl; lush green meadows were ringed by woods and

wild orchards. About 10,000 years ago, the Kurdish desert was a 'paradisiacal

place', as Schmidt puts it. So what destroyed the environment? The answer is Man.

As we began farming, we changed the landscape and the

climate. (What a nut-ball statement this small society caused

climate change, to an apocalyptic level of turning a virtual paradise into a

rainless desert region. Environmentalists’ crazy statements and assessment are

taken without question, Yet in upstate

And so, paradise was lost. Adam

the hunter was forced out of his glorious

Of course, these theories might

be dismissed as speculations. Yet there is plenty of historical evidence to

show that the writers of the Bible, when talking of

This is a male boar

with all his teeth and under him appears to be a smaller female boar above

appears to be a wingless bird sitting and behind it is another two legged bird with

a long tail making the two appear to be dinosaurs. The round hole is curios, one wonders what fit in there?

Archaeologist

Klaus Schmidt poses next to some of the carvings at Gebekli

In the Book of Genesis, it is

indicated that

Likewise, biblical

In ancient Assyrian texts, there

is mention of a 'Beth Eden' - a house of

Another book in

the Old Testament talks of 'the children of

The very word '

Thus, when you put it all

together, the evidence is persuasive. Gobekli Tepe is, indeed, a 'temple in Eden', built by our leisured

and fortunate ancestors - people who had time to cultivate art, architecture

and complex ritual, before the traumas of agriculture ruined their lifestyle,

and devastated their paradise.

It's a stunning and seductive

idea. Yet it has a sinister epilogue. Because the loss of paradise seems to

have had a strange and darkening effect on the human mind.

Many of Gobekli's standing stones are inscribed with 'bizarre and

delicate' images, like this reptile (This appears

to be a lioness hungry with its ribs showing crouched and ready to pounce)

A few years ago, archaeologists at nearby Cayonu

unearthed a hoard of human skulls. They were found under an altar-like slab,

stained with human blood.

No one is sure, but this may be

the earliest evidence for human sacrifice: one of the most inexplicable of

human behaviours and one that could have evolved only

in the face of terrible societal stress.

Experts may argue over the

evidence at Cayonu. But what

no one denies is that human sacrifice took place in this region, spreading to

Archaeological evidence

suggests that victims were killed in huge death pits, children were buried

alive in jars, others roasted in vast bronze bowls.

These are almost

incomprehensible acts, unless you understand that the people had learned to

fear their gods, having been cast out of paradise. (But the bible says God saw nothing but evil and it repented Him that He

had created man, and He determined to destroy and blot mankind with the flood,

but Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord) So they sought to propitiate the angry

heavens.

This savagery may,

indeed, hold the key to one final, bewildering mystery. The astonishing stones

and friezes of Gobekli Tepe

are preserved intact for a bizarre reason.

Long ago, the site was

deliberately and systematically buried in a feat of labour

every bit as remarkable as the stone carvings.

The stones of Gobekli

Tepe are trying to speak to us from across the

centuries - a warning we should heed. (Environmental doom is the warning the author

sees here)

Around 8,000 BC, the creators of Gobekli

turned on their achievement and entombed their glorious temple under thousands

of tons of earth, creating the artificial hills on which that Kurdish shepherd

walked in 1994.

No one knows why Gobekli was buried. Maybe it was interred as a kind of

penance: a sacrifice to the angry gods, who had cast the hunters out of

paradise. Perhaps it was for shame at the violence and bloodshed that the

stone-worship had helped provoke.

Whatever the answer, the

parallels with our own era are stark. As we contemplate a new age of ecological

turbulence, maybe the silent, somber, 12,000-year-old stones of Gobekli

Tepe are trying to speak to us, to warn us, as they

stare across the first Eden we destroyed.

The age of there stones may be double the age

of what people calculate the age of man to be, we are not as worried about the

numbers here as the testimony here of what men were capable of doing much

earlier than science has ever acknowledged and that this still demonstrates a

young earth according to bible records.

- The Genesis Secret by Tom Knox is published

by Harper Collins on March 9, priced £6.99. To order a copy (P&P

free), call 0845 155 0720.

Gobekli Tepe: The

World’s First Temple

Predating Stonehenge by 6,000 years, Turkey

By

Andrew Curry

Photographs by Berthold Steinhilber

Smithsonian magazine, November 2008

Now seen as early evidence

of prehistoric worship, the hilltop site was previously shunned by researchers

as nothing more than a medieval cemetery.

Six miles from

Here we see one of the many circles that were built here. We also see a number of stone walls for either

houses or some kind of compounds that were carved into the rock. This place would have taken a great deal of

effort to build and we also note that this is not only pre-flood but

pre-pyramid and yet the construction is so detailed and seemingly out of place

according to science as this is supposed to have been build during the “Neolithic

period when men only had stone hand tools – Little more than rocks with chipped

edges and were hunter gatherers that wandered here and there following their

food,

This place explodes all of these scientific myths showing a highly

organized and sophisticated society that rivals what is seen thousands of years

later in Ancient

Part of the answer may be in “And Cain fled from the presence of

the Lord, and the Lord put a mark upon Cain to prevent men from killing him. So

that we suspect that he and his household went and lived under rocks and in

caves hidden from God and from men. To

live such a lifestyle one would end up being some sort of hunter gatherer and

wandering from place to place as the food supply rose and fell. So we are

suggesting here that Cain and his descendants lived a different lifestyle than

the artifices builders and writers of the rest of the children of men,

Interestingly Job speaks of meeting with a society of people that

lived in the wilderness under rocks and in caves that ate roots and plants in

an area (Gatherers) and presumably killed animals and ate them

(Hunters) and that they seem to have shared their food with each other for

mutual survival. Job declares these to have been criminals and outcasts of

society. Cain was a criminal and an outcast of society as well and more than

likely lived this kind of life style, the tools of which would have been the

bear essentials to get by.

"Guten Morgen,"

he says at 5:20 a.m. when his van picks me up at my hotel in

Schmidt points to the great stone rings, one of them 65 feet across. "This is the first human-built holy place," he says.

The map is important to help the reader place were this “city” is

located. As compared to maps showing the location of some of the oldest cities in

civilization like Sumner,

From this perch 1,000 feet above the valley, we can see to the horizon in nearly every direction. Schmidt, 53, asks me to imagine what the landscape would have looked like 11,000 years ago, before centuries of intensive farming and settlement turned it into the nearly featureless brown expanse it is today.

This looks to be a tail of something very big like a dinosaur, the tailed animal is too indistinct to hazard a

guess as to what it might be.

Prehistoric people would have gazed upon herds of gazelle and other wild

animals; gently flowing rivers, which attracted migrating geese and ducks;

fruit and nut trees; and rippling fields of wild barley and wild wheat

varieties such as emmer and einkorn. "This area was like a paradise,"

says Schmidt, a member of the German Archaeological Institute. Indeed, Gobekli Tepe sits at the northern

edge of the Fertile Crescent—an arc of mild climate and arable land from the Persian

Gulf to present-day

With the sun higher in the sky, Schmidt ties a white scarf around his balding head, turban-style, and deftly picks his way down the hill among the relics. In rapid-fire German he explains that he has mapped the entire summit using ground-penetrating radar and geomagnetic surveys, charting where at least 16 other megalith rings remain buried across 22 acres. The one-acre excavation covers less than 5 percent of the site. He says archaeologists could dig here for another 50 years and barely scratch the surface.

Another view of the crouching starving lioness showing her teeth

and paws, from this angle it appears to be getting a drink of water in the pool

between the stones.

Gobekli Tepe was first

examined—and dismissed—by

Unlike the stark plateaus nearby, Gobekli Tepe (the name means "belly hill" in Turkish) has

a gently rounded top that rises 50 feet above the surrounding landscape. To

Schmidt's eye, the shape stood out. "Only man could have created something

like this," he says. "It was clear right away this was a gigantic

Stone Age site." The broken pieces of limestone that earlier surveyors had

mistaken for gravestones suddenly took on a different meaning.

Schmidt returned a year later with five colleagues and they uncovered the first megaliths, a few buried so close to the surface they were scarred by plows. As the archaeologists dug deeper, they unearthed pillars arranged in circles. Schmidt's team, however, found none of the telltale signs of a settlement: no cooking hearths, houses or trash pits, and none of the clay fertility figurines that litter nearby sites of about the same age. The archaeologists did find evidence of tool use, including stone hammers and blades. And because those artifacts closely resemble others from nearby sites previously carbon-dated to about 9000 B.C., Schmidt and co-workers estimate that Gobekli Tepe's stone structures are the same age. Limited carbon dating undertaken by Schmidt at the site confirms this assessment.

The way Schmidt sees it, Gobekli Tepe's sloping, rocky ground is a stonecutter's dream. Even

without metal chisels or hammers, prehistoric masons wielding flint tools could

have chipped away at softer limestone outcrops, shaping them into pillars on

the spot before carrying them a few hundred yards to the summit and lifting

them upright. Then, Schmidt says, once the stone rings were finished, the

ancient builders covered them over with dirt. Eventually, they placed another

ring nearby or on top of the old one. Over centuries, these layers created the

hilltop.

Today, Schmidt oversees a team of more than a dozen German archaeologists,

50 local laborers and a steady stream of enthusiastic students. He typically

excavates at the site for two months in the spring and two in the fall. (Summer

temperatures reach 115 degrees, too hot to dig; in the winter the area is

deluged by rain.) In 1995, he bought a traditional Ottoman house with a

courtyard in

On the day I visit, a bespectacled Belgian man sits at one end of a long

table in front of a pile of bones. Joris Peters, an archaeozoologist from the

I am guessing that in the center of the picture is a child that was

buried or entombed alive.

But, Peters and Schmidt say, Gobekli Tepe's builders were on the verge of a major change in how they lived, thanks to an environment that held the raw

materials for farming. "They had wild sheep, wild grains that could be

domesticated—and the people with the potential to do it," Schmidt says. In

fact, research at other sites in the region has shown that within 1,000 years

of Gobekli Tepe's

construction, settlers had corralled sheep, cattle and pigs. And, at a

prehistoric village just 20 miles away, geneticists found evidence of the

world's oldest domesticated strains of wheat; radiocarbon dating indicates

agriculture developed there around 10,500 years ago, or just five centuries

after Gobekli Tepe's

construction.

To Schmidt and others, these new findings suggest a novel theory of

civilization. Scholars have long believed that only after people learned to

farm and live in settled communities did they have the time, organization and

resources to construct temples and support complicated social structures. But

Schmidt argues it was the other way around: the extensive, coordinated effort

to build the monoliths literally laid the groundwork for the development of

complex societies.

The immensity of the undertaking at Gobekli Tepe reinforces that view. Schmidt says the monuments could

not have been built by ragged bands of hunter-gatherers. To carve, erect and

bury rings of seven-ton stone pillars would have required hundreds of workers,

all needing to be fed and housed. Hence the eventual

emergence of settled communities in the area around 10,000 years ago.

"This shows sociocultural changes come first,

agriculture comes later," says

This looks like a male panther

What was so important to these early people that they gathered to build (and

bury) the stone rings? The gulf that separates us from

Gobekli Tepe's builders is

almost unimaginable. Indeed, though I stood among the looming megaliths eager

to take in their meaning, they didn't speak to me. They were utterly foreign,

placed there by people who saw the world in a way I will never comprehend.

There are no sources to explain what the symbols might mean. Schmidt agrees. "We're

6,000 years before the invention of writing here," he says.

"There's more time between Gobekli Tepe and the Sumerian clay tablets [etched in 3300 B.C.]

than from

Still, archaeologists have their theories—evidence, perhaps, of the irresistible human urge to explain the unexplainable. The surprising lack of evidence that people lived right there, researchers say, argues against its use as a settlement or even a place where, for instance, clan leaders gathered. Hodder is fascinated that Gobekli Tepe's pillar carvings are dominated not by edible prey like deer and cattle but by menacing creatures such as lions, spiders, snakes and scorpions. "It's a scary, fantastic world of nasty-looking beasts," he muses. While later cultures were more concerned with farming and fertility, he suggests, perhaps these hunters were trying to master their fears by building this complex, which is a good distance from where they lived.

This is

a real interesting stone which is shown no where else in either article. We see on the top flamingos, we see what

appears to be water with waves in it and some indication of palm trees on the

corners of the stone.

Danielle Stordeur, an archaeologist at the

For his part, Schmidt is certain the secret is right beneath his feet. Over

the years, his team has found fragments of human bone in the layers of dirt

that filled the complex. Deep test pits have shown that the floors of the rings

are made of hardened limestone. Schmidt is betting that beneath the floors

he'll find the structures' true purpose: a final resting place for a society of

hunters.

Perhaps, Schmidt says, the site was a burial ground or the center of a death cult, the dead laid out on the hillside among the stylized gods and spirits of the afterlife. If so, Gobekli Tepe's location was no accident. "From here the dead are looking out at the ideal view," Schmidt says as the sun casts long shadows over the half-buried pillars. "They're looking out over a hunter's dream."

This looks like a running cow or wildebeest with its horns.

Andrew Curry, who is based in

Berthold Steinhilber's hauntingly lighted award-winning photograhs of American ghost towns appeared in Smithsonian

in May 2001.